Political Orientation

The old fishing launch slides alongside the wooden quay in Alatau. Doug, a young Australian farmer who lives near where we have Moira anchored in Samarai, cuts the fuel to the ear splitting diesel, "Krikey, it's always hot as hell here."

It is, too. A close, wet, steam-room kind of heat. It deflates the brain.

We secure the boat and trudge up from the waterfront. A real mudhole; perfect place to stick the capital of the Milne Bay Provence of Papua New Guinea.

"My dad was here during the war," Doug says as we walk the muddy road to town, "Some idiot put our main Australian base at the head of the bay, in the bloody mangroves. Dad always said it was hell building an airstrip in the hottest swamp on Earth."

The muddy coast road turns into a muddy main street lined on both sides with ugly corrugated steel buildings. Steam seeps from the mud in the awful heat. A series of old, colonial style buildings stand against the steeply rising jungle at the edge of town. Doug says these are the government compound. "After the war everybody moved out here from the base to get away from the heat," Doug chortles, "Then everybody moved to Samarai to get away from the heat of this place. Now they are moving everything back here again because of the airport. Bloody stupid."

"Yeah. Samarai is much nicer than this place." I wipe my sunglasses, the sun-block cream smearing greasily along the lenses. "What time do I meet you back at the boat?"

"Oh, what about 3?" He saunters off into the steaming heat, squinting at his shopping list.

I shuffle limply up the street to the government buildings. At least there are a few shade trees here, and a lawn of sorts, so it is fractionally cooler. Inside the main administration building a young, harassed, Melanesian sits in a cluttered office handing down the decree of the day to a motley crew of casual young bucks. They ignore me. Eventually he finishes and the young men wander off in different directions. He invites me into his office, smiling, saying, "You must be Doctor Uhhh."

"Chesher," I supply, shaking his offered hand. He gives me a soft touch, the standard Melanesian handshake..

"Yes, of course. We heard you might be coming by. My name is Rodney Abajai. I believe you would like an appointment with Vernon Guise, the Premier."

Within an hour he shows me into the large colonial headquarters from which Mr. Guise directs the government of the Milne Bay Provence. The Premier is an older PNG man who immediately gets down to business. "I understand you have come to do some fisheries research."

"Yes. The National Fisheries Division asked me to do a survey of Gold Lipped Pearl Oysters near Tagula. The pilot pearl culture project in Samarai, run by Dennis George...."

"I know Mr. George," He injects.

"Of course. Well, his project has shown he can grow fine pearls at his Samarai pearl center. The original plan for the project called for extending the pearl growing activity from Mr.George's pilot project to nearby villages. Village pearl culture centers are to be set up in several areas. Tagula is supposed to have the first village farm. But nobody really knows if there is a large enough population of pearl oysters to support a major commercial operation. So, I'm supposed to go look."

"I see." the Premier nods. "Have you talked with Dennis Young? He's our provincial planning officer. I believe he has some thoughts on the pearl business. And he can give you people to contact in Tagula. How long do you plan to be here?"

"Well, that depends." I answer. "After the Gold Lip survey we hope to do some additional surveys for the Fisheries Division on commercial invertebrates of the Milne Bay Provence; lobsters, trochus pearl shell, green snail, giant clams, black coral and perhaps even sponges. As you know the Fisheries Division has funds to build a series of freezer plants along the coastline of PNG and they want to build one in Misima even larger than the first one in Kupiano."

"Although plans are already in the works for the station, I believe it would be a good idea to conduct a survey of what stocks of commercially valuable animals are actually on the reefs to support such fisheries stations." I stop and consider if I should elaborate on this or not and decide not to.

"So I might be here a total of six months or perhaps even a year." I conclude.

He gets a distracted look on his face which I assume is a prelude to dismissal. After a few pleasantries he sends me off to see Mr. Young, the planning officer. My guide leads me through the heat of the mud main street to a tin-roofed general store. We trudge past shelves of canned goods, machetes, and kerosene lanterns into a cluttered office in the back. The guide points inside and wanders back into the store. I peek in and see a big, paunchy man, in his mid 40s. with shoulder-length blonde hair. "Mr. Young?"

Mr. Young it is. He is an Australian but he gives me the impression he has been here for many years (maybe even born here). He seems to know about me and is full of information about Milne Bay, chatting openly about this and that. Finally his rambling, but pleasant, conversation ends with the surprising statement, "You really must extend your pearl oyster survey to the Trobriand Islands."

"They need the pearl oyster center there more than Tagula does," he says, "You know of course they once had the best pearl industry....well, the only pearl industry.... in PNG not long ago. Buyers used to come from Europe and especially Russia, to get the famous black pearls of the Trobriands."

"I thought that died out in the fifties." I say, demonstrating at least some local research. "I was under the impression they simply overfished the stocks and exterminated the oysters."

"Well, that's what we need to find out, isn't it?" he beams at me and winks, "Why you should go and survey there?"

"I'd be happy to. But I can only do what National Fisheries is willing to support. If you recommend the survey extension to the National Fisheries people and they approve, we'll do it."

"Wonderful! I will. Now, lets see. When you go to Tagula you must stop at Nevani to visit Dusty Miller. He was born here in Alatau. An old man, now, but full of information. And in Tagula, look up Father Young and Mathew Paulisbo."

At three I am waiting on the old wharf, watching a multitude of decrepit and ageing interisland boats make ready to go wherever it is they are heading. Doug appears right on time and we hop onto his small fishing boat. As he gets ready to hand crank the little Yanmar diesel I ask if the boat was built here. He stands up and gives me one of those Aussie looks and says, "Waddya think, Mate?" With a single heave the unmuffled wham of the engine heralds our departure for Samarai. No chance of talking with the engine going. I settle back on a heap of sacs and relax. The twin-banger japanese diesel vibrates the whole boat. It's a wonder the nails don't fall out.

Samarai is a world apart from Alatau. Alatau is up on the northwest coast of Milne Bay, where it is grotty in the extreme. The hot southeasterly trades pile up along the steep mountain ridge forming the northern part of the bay. As the wind lifts over the ridge it cools slightly and dumps rain onto the coastal area. Hot and wet.

I look back at the heat shimmering green coast and think of Port Douglas and Lee Lafferty. Lee is half American Indian and had the knack of seeing nature signs in a special way. One day he drove me into Cairns and we stopped along the coastal road. The wind was blowing onshore.

"Look," He said, pointing out to sea, "You can see the wind piling up against the land. I've seen it extend 20 to thirty miles offshore when conditions are just right." He turned to look at me and smiled, "Not many people ever notice that."

I stared out to sea and at first couldn't understand what he was talking about. Then I saw it. The wind was blowing hard from the southeast but there was a calm area close to shore. Out about a quarter of a mile there was an actual line on the sea where the wind lifted from the water, riding up and over the mass of air piled up against the cliff-like face of the coast. I had never noticed it before. It was amazing. I could see the invisible wind by its track on the sea. I could see how it hit the land and churned low against the water, how the sheaf of ocean air rode up over the coastal undertow. Lee and I stood there a long time, just looking.

Doug's little boat crosses Lee's wind line about five miles from Alatau and we have a little cool breeze again. Alatau is caught in an eternal undertow, created by forces the people who live there never notice or understand.

In a way, this seems to be a political statement, too. Since PNG got its independence from Australia the larger undertow of forces created by the enormous island of Papua New Guinea dominates what actually happens out here in the provinces. Bureaucrats in Port Moresby decide Alatau is a better center of government because it is close to the airport. So the government offices are expanded here, removed from Samarai. And the provincial government is then run by men who are constantly heat fatigued.

Samarai, where the colonial government used to sit in comfort, is a tiny island sitting in the middle of China Strait. It is cool and pleasant as well as a natural cross-roads for water commerce. In the old days, they called Samarai the Pearl of the Pacific. A pretty little colonial town still covers almost all of the little round island. It is still an official port of entry for PNG. Moving the government centre to Alatau probably made lots of good sense to the politicos in Port Moresby but it's done nothing for the people here. I have the feeling lots of decisions have, and will, be incorrectly made by the National/Provincial government arrangement here. And most people will never know why their lives get screwed up - just as most of the people in Alatau don't know how or why they come to live in such a hot, muddy place.

Peter Wilson and the National Fisheries Division are part of the new PNG independence, that cliff standing behind the people of the provinces making unseen changes in their lives; protecting yet deadening the atmosphere, creating unforecasted precipitation which in turn creates a sticky muddy situation.

To the north of us, as we chug southeast across Milne Bay, a maze of islands hump gray-green in the vast calm bay. Beyond these are the large isles of Normandy and Fergusson and then - after that -the fabled Trobriand Islands; The Isles of Love. Our old launch put-putts for hours accross the huge, deep Milne Bay.

Pete and I have been friends for a decade: since he was the head fisheries officer for the Trust Territory of the Pacific, based in Palau. I was chief scientist for a U.S. Department of the Interior survey of the Crown of Thorns starfish in the North Pacific. A study resulting in funds and equipment for Pete and some interesting adventures for the two of us in Palau.

Pete is from Hawaii. Physically, he's a rogue male type. A big man with an "all American Football Hero" look about him. Strong and powerful, outgoing and dynamic. The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization hired him to head up the Papua New Guinea Fisheries Development Program.

Fisheries Management courses in grad school teach that the standard first step in a fisheries development project is to build fisheries collection stations with freezers. You can't develop a fisheries without a network to gather the product and get it to market. Oh sure, you have to have fishermen and boats but they can't survive financially without a way to warehouse and then move the product.

In the FAO plan, fisheries products caught by local fishermen will be sold to a coastal network of freezer plants and then shipped to Port Moresby and either exported or sold to the people of PNG to cut down on the need to import foreign fish products.

I can still see Peter in his office, his big chin stuck out with determination, a fighting grin on his face. National Development! The villagers will have work and pay and there will be INDUSTRY with boats and buildings to generate INCOME and cut down on imports and make PNG more SELF-SUFFICIENT and INDEPENDENT. OK team, Lets get out there and win!

The plan calls for a fisheries station every 64 miles of coastline. The first one has already been built in Kupiano, the district capital for the province just east of Port Moresby. The next one will be built on Misima, a small island north of Tagula. As Pete described the idea he rummaged around on some cluttered shelves in his office and produced a lovely glossy brochure FAO had printed up for them. It's blue cover showed a school of barracuda underwater. "Here, this will brief you on the project," he said, handing it to me with a fist the size of a ham.

"Hey, really nice, Pete." I thumbed through it. "Very professional". I stopped on a page which said, in essence, the only good fish is a dead fish. Uncaught fish are everybody's loss. Humph. Not much biological theory there. I turn to the budget. Wheeew! "How do you know there is enough fish around Misima to support the fishery?" The budget which gave a figure of some K500,000 (about $650,000 US) for the construction of a plant. No doubt an underestimate as cost overruns are the norm in PNG (as everywhere).

"Well, have a look at the map!" Pete waved a muscular arm at the map of Papua New Guinea on the wall behind his desk. "Look at the size of that lagoon around Tagula! Nobody's commercially fishing it. There are hundreds of islands, thousands of reefs. Untouched. All they need is a place to sell their product, a way to get it to market. Don't worry, there's plenty of product!"

I looked at the map, nodded my head and smiled, "Looks great, Pete, but don't you think it would be a good idea to survey the stocks to have some idea of what's really there? For all you know those reefs might have very little of commercial value on them. Or the fish and invertebrates could be so spread out it will be uneconomical to get the product to market."

"Well, sure. We'll do something, but it's not really a priority item." Pete's confidence was overwhelming.

"Look Pete," I was underwhelmed by the evidence, "I have a proposition. I'll survey the reefs in the area if you'll provide a vessel, food, and local transportation for some divers who will come to help me do the survey work."

"How much would you charge?" He said, looking serious. "We really haven't budgeted for any surveys...."

"I wouldn't charge anything. Strictly volunteer. There is an organization I worked with in the States called Earthwatch which finds volunteers for field projects of worthy cause. Helping with the fisheries national development project would be an excellent project. It takes a lot of people to survey a large reef area. The people would love to come and dive those reefs - I mean, how many people get the opportunity to dive virgin reefs like those?" I said waving my hand at the chart. "There is no commercial dive service into those areas. Divers from the US would love the opportunity and would pay their own way here. You help out with a boat to get the people down there and we'll do your survey for the pleasure of doing something constructive and enjoyable."

"Hey!" Pete grinned, "You've got a deal!" We

shook hands. That was months ago. Now it is all happening.

Doug turns his boat into China Straits just as the sun dives for the horizon.

There are reefs and strong currents throughout the network of small islands and only those with a lot of local knowledge or no brains at all venture out on the sea at night. Or even in the late evening.

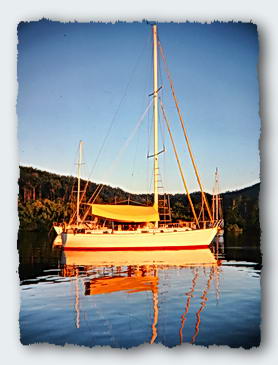

As the little boat pulls up alongside Moira I feel a thrill run through me. Moira is beautiful in the orange glow.

A beautiful boat, with Freddy, waiting to catch the line from the launch, smiling in the sunset.

An exciting an worthwhile project in an unexplored underwater wilderness lying just over the horizon.

What more could anyone want?